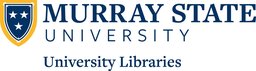

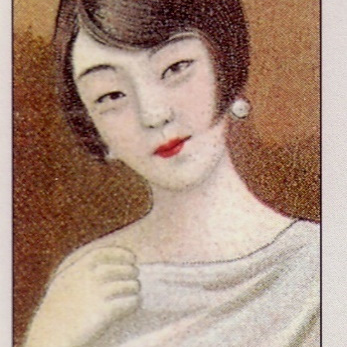

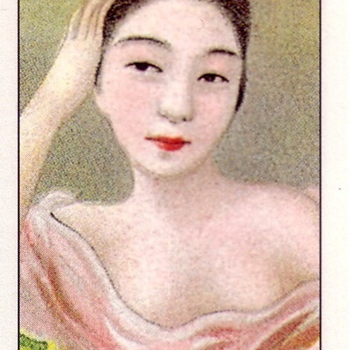

China’s rapid departure from Qing era modesty manifested itself in the introduction of the semi-nude beauty as a popular motif in cigarette cards beginning in the late 1920s. This, of course, had been employed by western artists from as far back as the 16th century, but was completely alien to China. Low cut or skin-exposing clothing for women was completely taboo into the 1920s, but the new Nationalist Party (KMT) government established late in the decade[1] tried to grant a limited number of new freedoms to women as part of its broader modernization agenda. These included new laws that allowed women to inherit property and made divorce possible, along with the creation of a Women’s Department and the inclusion of a pair of women on the party’s central committee.[2] The government followed up on the 1912 foot binding ban with a similar prohibition on breast binding in 1927.[3] Unsurprisingly, cigarette card makers immediately celebrated the arrival of the natural breast movement by making the “one bare breast” an especially popular new motif.

The natural breast movement was a significant marker in the quest for the liberation of Chinese women’s bodies even if it did come sanctioned by a conservative government. Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek’s New Life Movement kicked off in 1934 as a government-led civic movement that actively promoted a new standard of natural female beauty, including natural feet and breasts along with healthy bodies. Some have criticized it for promoting a Confucian-Christian-traditional approach to womanhood that could be described as a form of “fascist puritanism” that just so happened to create new opportunities for women in sport and leisure.[4]

At the same time, the KMT regime frowned on supposedly frivolous material pursuits. It encouraged the people to turn away from western fashion trends and shop like patriots from Chinese producers. This obviously served the self-interest of big Chinese businesses, which tapped into anti-imperialist sentiment in the runup to war with Japan as a marketing tool. The “buy local” boycott campaigns of this era, such as the government’s National Products Movement[5], centered on nationalistic pitches directed at China’s female consumers. It did not attack western habits encouraged by commercial advertising per se so much as it encouraged consumers to switch over to inferior made-in-China competitors.[6] Historian Karl Gerth writes the simple act of smoking cigarettes domestic producer placed millions of Chinese directly in the midst of battles to nationalize the country’s emerging consumer culture.[7] Advertisers guided Chinese smokers to associate foreign brands with luxury and style, while Chinese producers eventually countered with commercial images that blended modernity and nationalism in subtle ways.[8]

The 1930s also saw brought a new expectation that young women would participate in state-sanctioned athletic activities as a form of physical training. Many urban women embraced this development as a means of gaining access to a new public space, sporting facilities, in the hopes that this would promote gender equality[9]even if it was ushered in by an authoritarian government that envisioned women as active participants in a war of resistance against foreign occupiers. Japan precipitated an international crisis in 1931, the Mukden Incident, that it used to seize control of resource-rich Manchuria. In the years that followed there were sporadic military clashes between Chinese forces and Japanese military units stationed in the country that threatened to escalate into full blown war right up until the moment it finally broke out in the summer of 1937. In the interim, the government attempted to mobilize Chinese women as a military resource, an effort that Chinese cigarette card producers consciously assisted by disseminating images of women in sportswear participating in traditional and modern sports. Cigarette card advertisers did see in this a more self-serving end. As Antonia Finnane writes, these new female sports-themed cards of the 1930s “perpetuate the stationary pretty-girl image as girls invitingly stand next to a bicycle with one foot on a pedal or sit in the country-club garden holding a tennis racket, or sit on the beach, or hold a riding crop while standing next to a horse, or pose alluringly, poolside. Most often this was another opportunity to exploit a now legitimate display of bare arms and legs, and shapely torsos.”[10] These images feature women engaged in newly state-sanctioned physical actives while revealing as much skin as the first western cigarette cards introduced to China almost 50 years earlier.

The fight for women’s rights enjoyed support from commercial advertisers and cigarette card makers right up to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. The production of cigarette cards slowed down markedly from the late 1930s due to wartime exigencies. Shanghai, the country’s cosmopolitan commercial heart, fell to the Japanese soon after the war began in the summer of 1937 and was isolated from the country at large until the fighting ended in 1945. Any hope that the city would regain its prewar prominence as a trendsetter in the country’s cultural life were dashing with the subsequent Chinese Civil War, which exacerbated paper shortages and created hyperinflation that dramatically material costs of advertising. Many tobacco companies gave up on producing cigarette cards altogether. The final set to come from a Chinese company in the first half of the century was an illustration of China’s Resistance War against Japan, which was issued by Shanghai Yuhua Cigarette Company in 1946.

The savage, protracted, and all-encompassing nature of the China’s War of Resistance against Japan (1937-45) meant that intellectuals and advertisers largely reoriented towards bare survival at the expense of efforts to promote new roles for modern women. China’s Civil War concluded with a decisive communist victory that a profoundly negative impact on freedom of expression and commercial advertising. The newly victorious CCP had its own clearly defined ideas about the role of women in the new society it planned to build and had even less tolerance for dissenting views that the Nationalists had during the Nanjing Decade. Gone by the 1950s were Hollywood-influenced fashions and western consumer habits, replaced by omnipresent Soviet-inspired unisex and mono-color costumes. Women lost the right to express themselves through their clothing, hair, or make-up, and no commercial outlet dared push back against the regime.

Nevertheless, the visual references in this project illustrate how Chinese women’s images experienced huge transformations in the late Qing and Republican era. These changes coincided with almost all of the major historical events that shaped China during this period. Advertising in general, and the medium of cigarette cards in particular, was a vehicle through which business successfully promoted new roles and new freedoms for Chinese women. In its own way, the artistic styles of these images not only reflected the changes in Chinese politics, the economy, and values of the nation, but also illustrated Chinese women’s liberation over the course of different historical periods.

[1] The “Nanjing Decade” (1927-1937), also known as Nanking decade or the Golden decade, started with the unification of China brought about by Chiang Kai-shek and ended when the Nationalist government lost its’ capital, Nanjing, at the outset of the Second Sino-Japanese War. China was relatively stable during this period and made considerate progress.

[2] Sharon Sievers, “Women in China, Japan, and Korea,” in Barbara N. Ramusack and Sharon Sievers (eds.), Women in Asia: Restoring Women to History (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press), 212.

[3] Finnane, Changing Clothes in China, 161.

[4] Louise Edwards, “Policing the Modern Woman in Republican China,” Modern China 26, no. 2(2000): 120.

[5] The National Products Movement (1900–1937) was a widespread social movement designed to stoke of Chinese nationalism. It promoted the purchase of Chinese-made products over foreign competitors, thereby offering people of all classes a means of resisting imperialism and expressing their loyalty to the nation. Karl Gerth has argued that this movement created a nationalistic consumer culture that drove modern Chinese nation-making. This movement enjoyed the support of the Nationalist government. The Chinese National Product Exhibition in Shanghai in 1928 and the Chinese National Product Exhibition in Hangzhou in 1930, both of which were organized in conjunction with the Nationalist government, showcased the movement’s import substitution ideology. See Liu Li and Fan Hong, The National Games and National Identity in China: A History (New York: Routledge, 2017), 41.

[6] Xin Zhao and Russell W. Belk, “Advertising Consumer Culture in 1930s Shanghai,” Journal of Advertising 37, no. 2, 2008): 51.

[7] Karl Gerth, China Made: Consumer Culture and the Creation of the Nation (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003), 56.

[8] W. Tsai, Reading Shenbao: Nationalism, Consumerism and Individuality in China 1919–37 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 30.

[9] Wu Huaiting, “The Marketing of Modern Women in Early Twentieth Century Shanghai: The Creation of Consuming Modernity and Nationalism in Advertising,” (PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 2012), 32.

[10] Finnane, “What Should Chinese Women Wear?: A National Problem”, 118.