China had great cultural change imposed on it by outside western forces in the early 20th century just as various segments of the population began engaging in rigorous debates over how it could potentially impact their lives for the better. The possible scope of this change broadened considerably during the decade after the 1911 Xinhai Revolution and the role of Chinese women was very much in play along with so many aspects of Chinese life. This revolution brought about the collapse of the Qing Dynasty, but it failed to provide as clean of a break between the pre-modern and modern era as many reformers had hoped. It was, however, a clear accelerator for social change and new ideas. China’s intellectuals, all male but progressive by the standards of their time and place, had already begun debating where women fit in society before the revolution and continued to promote new roles after its unsatisfying conclusion. There was in World War I era China a prevailing social conservative ideal of liangqi xianmu (良妻賢母 good wife, wise mother) that these intellectuals challenged with the concept of xin nuxing (新女性 New Woman) and modeng nulang (摩登女郎 Modern Girl) across cultural media and in advertising. They promoted a vision of the New Woman of the post-revolution period as a modern, progressive, educated nationalist who was politically active and eschewed the superficial distractions of so many in China’s burgeoning professional classes. She was presented as both cosmopolitan and modern, but also trendy, fashionable, and open to western influences that were encouraged by and reflected in advertising of the era.[1]

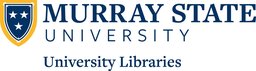

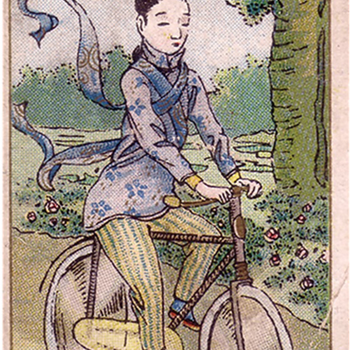

A popular 1914 BAT calendar designed by talented artist Zhou Muqiao (周慕橋 1868-1923) offers us an early representation of this idea of the New Women and inspired his contemporaries to create images of females who had adopted non-traditional and western-style activities and clothing.[2] Huaiting Wu argues that “the omnipresence of advertising across different media makes it a powerful part of public discourse… [that] shapes people’s consciousness of reality and their perception of behaviors. Analyses of advertisements, therefore, provide valuable information for understanding public discourses and related power relations.”[3] We should conceive of mass advertising of the sort seen in cigarette cards as both an idealized construction of reality as well as a reflection of ongoing changes in society.

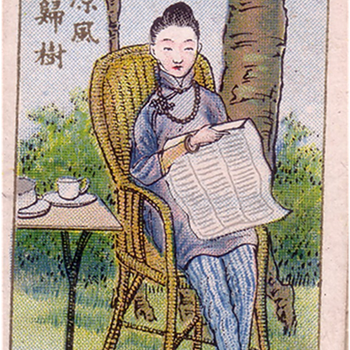

Some trendsetting Chinese women of the early 20th century took the radical step of wearing men’s style clothing in public to draw attention to their aspirations for gender equality. The primary inspiration for these campaigners was the iconic Qiu Jin (秋瑾 1875-1907), a passionate revolutionary who called for a form of vigorous national rejuvenation that put women’s liberation at the core of its aims. Qiu earned notoriety as China’s best-known cross-dresser, one who often took to the streets of Beijing in both Chinese and western men’s clothing to draw attention women’s exclusion from military, political and intellectual life.[4] She claimed that dressing like a man would eventually make her more masculine and, therefore, strong. She wrote, “My aim is to dress like a man! If I first take on the appearance of a man, then I believe my mind too will eventually become like that of a man!”[5] Qiu was not an outlier; in fact, one often saw women in traditionally male military uniforms during the immediate aftermath of the 1911 revolution and prostitutes in particular took to men’s clothing as a sly protest against the moralistic hypocrisy of those who solely criticized women’s role in what was obviously a two-party business arrangement.[6] The inclusion of female Chinese crossdressers in cigarette card sets was certainly an edgy marketing move, but it did pay off by winking at allyship with female consumers.

The post-revolution Nanjing government responded to pressure for change from feminists, writers, and western missionaries by finally placing a ban on foot binding in 1912, followed by a national campaign to encourage compliance. The new freedoms that came with this ban were depicted in cigarette card advertising, which began to feature vibrant women who were visibly cherished life instead of merely enduring it. Cigarette advertisers started to depict natural-sized unbound feet on women who wore smiles, peddling sexualized images of women for their own commercial gain, albeit with the ancillary benefit of normalizing the end of footbinding for a mass audience and helping consign this very painful vestige of the traditional Chinese feminine beauty ideal to the dustbin of history.

Western fashion began to gain popularity in China in the aftermath of the failed Boxer Uprising from 1899 to 1901, particularly for women, and there was a widespread rush for tight clothes with narrow sleeves or Western-style cloth with lace, buttons, and fur after World War I. Chinese women enthusiastically adopted western-inspired bangs and short haircuts in the 1920s, while cigarette advertisements captured this fascinating early intersection of Chinese culture and Western style. The highest profile celebrities of the era blissfully embraced their role as Modern Girls free to pursue their glamorous big city lives free of traditional restrictions.

New fashions were not the sole preserve of the rich and famous. The female student uniform, also called “new civilized clothing,” was adopted around the time of the May Fourth Movement in 1919. The impetus for a modernized school uniform came from educated women who lobbied for the adoption of occupation-based clothing of the sort that western female students, teachers, and nurses wore. Students were a logical starting point because they were legion while professional career women were few and far between. This new civilized clothing was made up of a white jacket and black skirt combination that became so popular that it spread beyond campuses to the general female population. Once again, cigarette cards circulated images of women in this new form of dress for a mass audience, which in turn helped normalize the idea of modern Chinese women entering new roles in the public sphere.

[1] Sarah E. Stevens, “Figuring Modernity: The New Woman and the Modern Girl in Republican China,” NWSA Journal 15, no.: 3 (2003): 84.

[2] Laing, Selling Happiness, p.102.

[3] Wu Huaiting, “The Construction of a Consumer Population in Advertising in 1920s China,” Discourse & Society 20, no. (2009): 147-48.

[4] Louise Edwards, Women Warriors and Wartime Spies of China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 56.

[5] Fan Hong and J.A. Mangan (2001), “A Martyr for Modernity: Qiu Jin – Feminist Warrior, and Revolutionary,” The International Journal of the History of Sport 18, no. 1 (2001): 38.

[6] Antonia Finnane, Changing Clothes in China: Fashion, History, Nation (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008), 192.